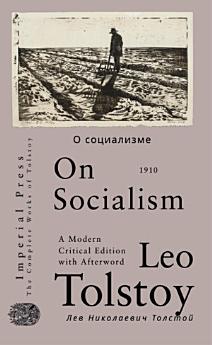

On Socialism

About this ebook

Composed in the last year of Tolstoy’s life and circulated in Russia as a standalone essay, On Socialism avoids the formulaic optimism that often colors utopian speculation, instead dismantling the philosophical foundations of socialism and its kin by exposing the inherent unpredictability of social evolution. Tolstoy refuses to grant that history moves according to knowable laws or that future forms of economic life can be rationally prescribed by theorists, arguing that all such schemes lead, by necessity, to violence and deception as soon as they are enforced through power. Social progress, for Tolstoy, cannot be orchestrated by either Marx or his critics, but must remain perpetually contingent on the moral choices of individuals; attempts to impose blueprints—whether capitalist, socialist, or otherwise—create strife and undermine the possibility of genuine communal life.

At the heart of Tolstoy’s argument is a philosophical distinction between the “religious-moral law,” shared by all major traditions and expressing itself in the injunction not to do unto others what one would not wish for oneself, and the endless, conflicting directives issued by political and social doctrines. The essay weaves an extended analogy: laborers who invent their own purposes for the tasks assigned by their master produce only disorder and discord, just as societies driven by competing ideologies succumb to violence and misery. Tolstoy’s closing challenge is not a call for revolution, but an exhortation to reject superstition—whether of church, state, science, or progress—and to embrace an ethical life grounded in the “reasonable religious worldview,” a foundation he claims alone can dissolve the roots of exploitation, violence, and social decay. Far from aligning with the currents of his era, Tolstoy’s late voice calls his readers to a radically undogmatic and uncompromising moral autonomy, situating this essay as a lasting anomaly within the literature of social theory.