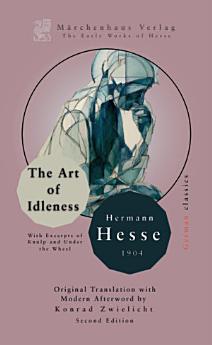

The Art of Idleness

The Early Works of Hermann Hesse Book 19 · Marchen Press

Ebook

170

Pages

family_home

Eligible

info

reportRatings and reviews aren’t verified Learn More

About this ebook

This early Hesse essay, written in 1904, was not published in his lifetime but first appeared in print posthumously under his estate’s care in 1973. Titled in the original German "Die Kunst des Müßiggangs", the work is a meditative reflection on leisure and creativity. In it, Hesse argues for the value of contemplative rest in contrast to society’s restless productivity, using lyrical prose and philosophical argumentation. The tone is calm and serious, blending moral observation with poetic description. Hesse’s style in this essay is thoughtful and introspective, evoking the spiritual influence and mystical leanings that characterize his later writing. This modern translation is combined with excerpts from Beneath the Wheel and Knulp which follow the same themes. In Beneath the Wheel, Hans is crushed by relentless academic pressure, illustrating the dangers of a life devoid of leisure and inner freedom. Knulp, by contrast, embodies the joy and spiritual richness of a wandering, idle life lived outside bourgeois norms. Both works echo Hesse's call to reject the "hurry hurry" mentality and embrace a slower, more contemplative existence. This new edition features a fresh, contemporary translation of Hesse's early works on making space for artistic development, making these early works accessible to modern readers from the original Fraktur manuscripts. Enhanced by an illuminating Afterword focused on Hesse's personal and intellectual relationship with Carl Jung, a concise biography, a glossary of essential philosophical terms integral to his writings (his version of Jungian Psychological concepts) and a detailed chronology of his life and major works, this robust edition introduces the reader to the brilliance of his literature in context. It not only captures the depth and nuance of Hesse’s thought but also highlights its enduring impact on the debates of the mid-20th century, contemporary culture and Western Philosophy across the 20th century and into the 21st. In these three works, the defense of “purposeless” creativity prefigures the psychoanalytic valorization of free association, while its critique of labor alienation anticipates Frankfurt School theorists. The work’s historical significance lies in its subversion of Wilhelmine Germany’s rigid work ethic, offering a clandestine manifesto for the era’s disaffected intelligentsia.

About the author

Herman Hesse (1877-1962) navigated a life shaped by psychological turbulence that fundamentally transformed his literary vision following his pivotal encounter with Carl Jung's analytical psychology. After suffering a severe breakdown in 1916 amid his crumbling first marriage and the ravages of World War I, Hesse underwent intensive psychoanalysis with Jung's student J.B. Lang and later with Jung himself, sessions that would profoundly alter his creative trajectory. This Jungian influence became evident in his subsequent works, particularly "Demian" and "Steppenwolf," where the protagonist's journey toward individuation—Jung's concept of integrating the conscious and unconscious aspects of personality—emerges as a central theme. Hesse's correspondence with Jung continued for decades, their intellectual relationship deepening as Hesse increasingly incorporated Jungian archetypes, dream symbolism, and the notion of the shadow self into his narratives of spiritual seeking. The writer later acknowledged that Jung's therapeutic methods had not only rescued him from psychological collapse but had fundamentally reshaped his understanding of human consciousness, enabling him to transmute his personal suffering into the allegorical quests for wholeness that characterized his most enduring works.RetryClaude can make mistakes. Please double-check responses.

Rate this ebook

Tell us what you think.

Reading information

Smartphones and tablets

Install the Google Play Books app for Android and iPad/iPhone. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are.

Laptops and computers

You can listen to audiobooks purchased on Google Play using your computer's web browser.

eReaders and other devices

To read on e-ink devices like Kobo eReaders, you'll need to download a file and transfer it to your device. Follow the detailed Help Center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders.